Today we acknowledge receipt of HP’s civil claim against the former management of Autonomy.

As readers will see from our comments below, we utterly refute the allegations made against us. HP has waged a three-year smear campaign riddled with half-truths and obfuscation. They have intentionally made the claims as complex and convoluted as possible. This is why, in the interests of transparency, we have posted a series of updates to this blog today so that everyone can see the allegations for themselves and fully understand our position.

There are three separate sections, which we set out below, as well as a downloadable PDF version of the letter from our lawyers Clifford Chance.

1. Lawyer’s letter containing preliminary detailed response to HP allegation

2. Our summary of the main allegations being levelled by HP

3. A reaction from Mike Lynch to this latest development in HP’s ongoing campaign against us

4. Downloadable PDF of lawyer’s letter (item 1 above)

The links above will take you directly to each specific post, or you can get to them by scrolling down the page.

1. LAWYER’S LETTER CONTAINING PRELIMINARY DETAILED RESPONSE TO HP ALLEGATION

In re Hewlett-Packard Company Shareholder Derivative Litigation

Dear Mr. Wolinsky:

As you know, we, along with Steptoe & Johnson, represent Dr. Michael Lynch. Hewlett-Packard Company’s (“HP“) decision to file in the referenced action (the “California Action“) the Particulars of Claim (the “Particulars“) filed against our client by various HP subsidiaries in the United Kingdom (the “UK Action“), a proceeding to which, quite notably, HP is not a party, is a continuation of HP’s transparent effort to generate one-sided publicity for its specious claims and false statements, avoid disclosure and engagement on the merits, bury HP’s own malfeasance, and insulate its directors and officers from liability.

We write to you now to make plain—as we have made clear to HP on several previous occasions—that the claims in the Particulars are without basis. While Dr. Lynch looks forward to unmasking the falsity and hypocrisy of these allegations in the courts of England (where, if at all, the matter belongs), in the interest of full disclosure, we request that, once the Particulars are unsealed, you amend your filing in California to include this letter, which sets forth below Dr. Lynch’s preliminary responses to the Particulars. In this way, the court, parties, and the public can have a fair understanding that the allegations in the Particulars are without basis and emphatically denied and that this matter will be fiercely contested in the courts of England.

INTRODUCTION

HP’s (notably unparticular) Particulars make clear that HP has had very good reason for its two and a half years of stalling, misdirection, and evasion regarding the details of its allegations against our client and other members of Autonomy Corporation plc’s (“Autonomy“) former management. Simply put, after two and a half years of apparent investigation—no doubt at a cost of many tens of millions of dollars to the shareholders of HP—it is clear on the face of HP’s own filings that its claims are baseless.

HP’s patchwork tale of alleged misconduct rests on a faulty foundation of false facts, unsupported inferences, and a misunderstanding and misapplication of the relevant legal and accounting standards. Nearly two and a half years after HP announced its write-down, it is clearer than ever before that HP’s claims are merely a tactic to obscure the true source of HP’s and Autonomy’s losses: the wrongdoing and ineptitude of HP’s own directors and officers.

That HP’s claims are without merit is plain from the preliminary response set forth below. But several points omitted from HP’s claims bear noting at the outset. In particular, the evidence shows that at all times:

- Autonomy was in full compliance with the law and applicable accounting standards;

- Autonomy employed a professional and experienced finance team that paid careful attention to ensuring that its accounts were properly stated;

- Autonomy was transparent with its deeply experienced and careful professional auditors team from Deloitte, who audited the precise issues HP appears to contest, and who, to this day, stand by the accounts;

- Autonomy had a dedicated, active, and experienced Audit Committee who met regularly with Deloitte to review Autonomy’s accounts and relevant policies; and

- Dr. Lynch, who is not an accountant, had little involvement in sales and in making the corresponding accounting decisions related thereto.

Accordingly, it should not be surprising that there is not one shred of actual evidence establishing any pre-acquisition misconduct by anyone at Autonomy, let alone evidence of fraud. There are no documents or witnesses—and HP has pointed to none—that demonstrate that any former member of Autonomy’s management acted with anything but honest intentions, good faith, and reliance on the professionals described above. This is hardly the stuff of a legendary fraud. In fact, in 2010 the Financial Reporting Review Panel (the “FRRP“) of the Financial Reporting Council, the regulatory body in England responsible for regulating accounts and accountants, reviewed many of the same transactions at issue here and found no basis for a continuing inquiry—as did Autonomy’s Audit Committee and its external auditors at Deloitte.

Despite the lack of any credible evidence of wrongdoing, HP first surfaced its opaque and spurious claims in November 2012. Around that time, it reportedly brought the allegations to the attention of regulators in the United Kingdom and the United States. Reflective of the dearth of actual evidence, well more than two years on, the UK’s Serious Fraud Office closed its investigation without charges, and Dr. Lynch was dismissed from the only active lawsuit in the United States that named him as a defendant.

Nor can HP’s far-fetched fraud accusations be reconciled with the fact that almost every senior member of Autonomy’s management eagerly stayed on at HP Autonomy after the acquisition. Does HP claim that the fraud was so cleverly hidden that Autonomy management could join HP secure in the knowledge that the misconduct would remain undetected, despite knowing that HP would have full access to Autonomy’s books and records? No. To the contrary, HP’s claims are purportedly based on the very books and records HP controlled the day the acquisition closed. And, regarding those books and records, HP conveniently fails to mention that despite the claimed $5 billion fraud, no cash is missing at Autonomy: Indeed, once all of the supposedly manufactured revenue is removed, Autonomy’s financials show over $450 million cash surplus. How is this fraud?

Yet another unexplained mystery is why it took HP two and a half years of ever-changing allegations to decide on a story that it is willing to tell in a pleading. The only constant in that time is the grinding of HP’s tired wagons circling around its own officers and directors—the very people who actually bear responsibility for the destruction of Autonomy’s value (as well as numerous companies before). Indeed, HP’s campaign of misdirection highlights its fear that its officers and directors will be found liable for the losses, culminating now in a plea to the judge overseeing the shareholder derivative litigation in California to forbid anyone from bringing any Autonomy-related claim against those individuals.

In reality, there is nothing mysterious about any of this. The simple truth is that HP’s losses were not caused by anyone at Autonomy. They were caused by HP’s own incompetence and malfeasance. HP has demonstrated once again its inability to make a potentially transformative acquisition work. It grossly overestimated the projected synergies to be realized from the deal, bungled the integration of Autonomy into HP, and then hid the whole thing from the market for as long as it possibly could. That is the real story of fraud here.

Pre-Acquisition: HP’s Quest for Autonomy’s “Almost Magical” Technology

After boardroom scandals, failed acquisitions, and instability in its executive suite, HP looked to the October 2011 acquisition of Autonomy to reverse its fortunes and transform itself from a low-margin hardware provider to a high-margin enterprise software company. In particular, HP anticipated that: (1) Autonomy’s IDOL software, which HP board member (and now CEO) Meg Whitman has called “almost magical,” could be combined with software from HP’s newly acquired structured-data solution, Vertica, to create an industry game-changing technology that could process both structured and unstructured data; (2) HP could leverage its global sales footprint and complementary hardware to drive Autonomy sales around the world; and (3) HP would, overall, use its low-margin legacy assets to drive high-margin Autonomy software sales.

HP was eager to finalize the deal without competition from other potential suitors, or exposing sensitive competitive information to competitors. HP’s bid reflected that. It was aggressive in its pricing, but reflected a reasonable value for Autonomy in the hands of a competent acquirer. However, HP’s officers and directors were well aware that HP was not a competent acquirer. At the time of the Autonomy merger, HP—and only HP—knew that (a) it was about to abandon its Palm operating platform, which it had acquired only a year earlier for $1.8 billion; (b) it was preparing to announce its departure from the PC market, its core business, which accounted for roughly one-third of its revenue; and (c) it was about to release poor earnings results and lowered guidance, which would certainly lead to a drop in the stock price. In fact, these announcements—made the same day the Autonomy acquisition was announced—resulted in a one-day drop of 20% in HP’s share price, reducing its market capitalization by $12 billion.

Post-Acquisition: HP’s Botched Integration and Desperate Search for a Scapegoat

The architects of the Autonomy acquisition were HP’s then-CEO, Léo Apotheker, and then-Chief Strategy and Technology Officer, Shane Robison. In September 2011, before the Autonomy acquisition was even completed, HP fired Mr. Apotheker and replaced him with Ms. Whitman. Mr. Robison left HP the following month. Thus, Autonomy was left to try to integrate into HP without the very people who had conceived of the acquisition and who were uniquely positioned to execute that integration. There was no handover of the integration plan, and key decisions made pre-acquisition were not implemented. HP did not even hire a new Chief Strategy and Technology Officer to replace Mr. Robison. In short, a period of chaos ensued at a critical time for the integration.

The damage was immediate and severe. Hundreds of key Autonomy employees left in the year following the acquisition. HP never integrated IDOL and Vertica to create the new product on which the acquisition was largely predicated. HP’s preexisting staff actively worked against Autonomy by marketing its competitors’ products, due to dysfunctional internal incentive structures. For example, HP salespeople did not receive “quota credit” or commissions for sales of Autonomy products, as they did for third-party software products, and HP’s Enterprise, Storage, Servers and Networking (“ESSN“) department refused to support Autonomy’s efforts to use ESSN hardware because sales to Autonomy did not count toward ESSN’s sales quota. HP prevented Autonomy from executing its own marketing strategy and repeatedly excluded Autonomy from participating in HP’s public relations events. HP did not provide Autonomy with the necessary sales and services support or staff, and HP’s Software department engaged in a power struggle with Autonomy leadership for control over the direction of HP’s software offerings. HP mishandled the pricing of Autonomy products, sometimes heavily discounting them to incentivize HP’s low-margin hardware sales and at other times marking them up significantly to boost the revenues of lagging HP departments. Perhaps most telling of the internal discord, HP staff refused to sell or recommend Autonomy products until Autonomy was “certified” for HP hardware, a process that was estimated to take a year.

Predictably, these problems caused a sharp drop in Autonomy’s historical close rates. Dr. Lynch provided Ms. Whitman with a presentation in May 2012 analyzing the reasons for this decline, including Ms. Whitman’s failure to control the infighting and dysfunction at HP. A few days later, Dr. Lynch was fired.

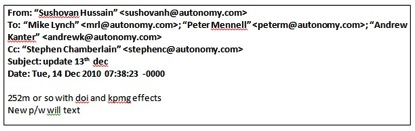

Faced with a crisis of its own making, HP chose to write down the value of Autonomy and to make unsubstantiated allegations of accounting irregularities against Autonomy’s former management. Those statements by HP to the market, beginning on November 20, 2012, and continuing to the present day, were false, and HP knows it. Since HP first announced the write-down, HP has struggled to explain the numbers underlying its claim. In that time, HP has busied itself conducting a supposed “investigation,” the result of which was pre-determined from the outset, to support its claims and scapegoat Dr. Lynch, Mr. Hussain, and Autonomy’s former management. That the allegations against former Autonomy management are unsupported is evident from HP’s ever-shifting rationales for its accusations. For example, HP claimed in November 2012 to have been unaware that Autonomy sold any hardware. By September 2014, HP conceded that it had been aware that Autonomy sold hardware but claimed not to have known of the type of hardware that Autonomy sold. In fact, HP knew about Autonomy’s hardware sales all along. Additionally, it appears that HP may be using its allegations against Autonomy’s former management and the accompanying re-characterizations of historical revenue to make improper claims for corporate tax refunds.

While we are still reviewing the Particulars, to which we will respond formally in court in due course, it is clear on the face of the Particulars that they are merely the latest evolution of familiar, and flawed, allegations that HP has pressed for the past two and a half years. What follows is a summary response to some of the core allegations made in the Particulars. We look forward to receiving and reviewing discovery from HP and are certain that documents solely in HP’s possession at the moment will further reveal the true folly of HP’s allegations.

I. AUTONOMY’S SYSTEMS AND PRACTICES

A. Autonomy’s Sales and Accounting Systems were Overseen and Approved Internally and Externally by Highly Competent, Independent Professionals

Throughout its life as a public company, Autonomy’s accounts and policies were reviewed by external auditors and judged to be compliant with applicable accounting standards. Specifically, for the years 2005 through 2010, Deloitte audited Autonomy’s annual statements, which were prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS“) as adopted by the European Union, the regime under which UK listed companies are required to report their accounts. Autonomy’s accounting and disclosure complied with IFRS. Autonomy’s external auditors at Deloitte also reviewed Autonomy’s quarterly and interim financial statements to ensure compliance with the relevant standards and rules. As such, Deloitte reviewed Autonomy’s financial statements for the first six months of 2011 and reported on July 27, 2011—just before the acquisition by HP—that it had no reason to believe that any aspect of the accounts had not been “prepared, in all material respects, in accordance with” the governing standards.

Deloitte’s judgment was based on all of Autonomy’s relevant financial information. Deloitte’s practice was to review all sales contracts and invoices for more than $1 million and a sample of contracts for more than $100,000. In addition, each quarter Autonomy’s management provided a report to the Audit Committee, with a copy to Deloitte, describing (among other things) Autonomy’s financial results, significant events, software and hardware sales, bad debts, and cash collection.

Deloitte reported directly to Autonomy’s independent Audit Committee, which was appointed by the company’s non-executive directors. The committee was responsible for monitoring the company’s financial statements and public announcements relating to financial performance. In 2009, the committee included Barry Ariko, a former Silicon Valley hardware and software executive. In 2010 and 2011, the committee was chaired by Jonathan Bloomer, a chartered accountant, former senior partner at Arthur Andersen, former CEO of Prudential, former Chairman of the Financial Services Practitioner Panel of the Financial Services Authority (“FSA“), and current member of the UK Takeover Panel. Each quarter, Deloitte provided the Audit Committee with a detailed report analyzing all significant accounting decisions for the relevant financial period, and the committee met quarterly with Deloitte to review Autonomy’s financial statements and discuss significant accounting risks, including revenue recognition and disclosure. Each meeting included a “no management present” session with Deloitte. As CEO, Dr. Lynch was not a member of the Audit Committee, did not attend Audit Committee meetings, and was not responsible for accounting decisions.

Notably, revenue recognition was identified as a key focus in Deloitte’s reports to the Audit Committee and, in each case, the Audit Committee approved Autonomy’s financial statements and Deloitte issued unqualified audit opinions.

Nonetheless, HP appears to contend, in paragraph 133.5 of the Particulars, that the location of Dr. Lynch’s and Mr. Hussain’s desks somehow demonstrates a shared awareness of, and responsibility for, all the transactions at issue and their related accounting. The reality is that Dr. Lynch and Mr. Hussain relied on Autonomy’s extremely experienced auditors and Audit Committee, professional sales force, technical team, finance team, and attorneys. This argument seems especially ludicrous given that Dr. Lynch and Mr. Hussain had separate offices, with the exception of one Autonomy location that utilized an open-plan office—far from the den of conspiracy implied by HP.

B. End-of-Quarter Deals are Common and Legitimate in the Software Industry

HP makes much of the fact that Autonomy often closed deals at or near the end of a fiscal quarter. That misplaced emphasis simply illustrates how out of touch HP is with the nature of the software business that it supposedly has been operating for three and a half years now. As everyone who has even a passing familiarity with the software industry knows, it is common for deals to be done toward the end of or on the last day of the quarter. The reason is simple: As in any business, customers prefer to hold out for the best deal for as long as possible, and because software can be delivered instantaneously, these negotiations can continue right up until the closing minutes of a quarter. HP’s ignorance of this is bemusing, especially in light of its purported laser-like focus on accounting rules. This practice is so commonly accepted and well known that it is described in accounting treatises. And, despite HP’s professed ignorance, the truth is it engages in the same practices.

C. Setting Revenue Targets is a Proper Business Practice

HP also complains (in paragraphs 135.2 and 135.3 of the Particulars) that Autonomy managed its sales pipeline in order to hit its revenue target for each quarter. Again, this allegation evidences a shocking naiveté about the way the software business—and, indeed, any publicly traded company—actually works.

Autonomy was a FTSE 100 company—one of the largest 100 companies listed on the London Stock Exchange (“LSE“) by market capitalization. As with most LSE companies, and especially those in the FTSE 100, market analysts tracked Autonomy’s financial performance and came to a “consensus” regarding the company’s anticipated revenues and share price for each quarter, half-year, and year-end, based both on analysts’ independent research and on Autonomy’s financial announcements. Autonomy, like its peers, monitored these numbers and aimed to hit its projected targets for each quarter, in order to manage market expectations and rationalize growth. Results that fell far short of expectations obviously could lead the market to conclude that the company was in trouble, while an anomalous quarter that far exceeded projections could lead to unduly inflated expectations for future quarters.

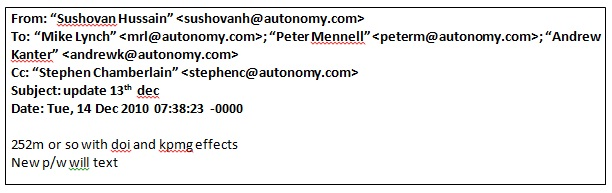

Autonomy’s management of its sales pipeline was proper. Indeed, if it had not done so, it would have been vulnerable to allegations of management incompetence. Nor did Autonomy do anything out of the ordinary (much less fraudulent or illegal) to achieve those targets. Indeed, the company’s annual report and accounts repeatedly described its efforts in this regard. For example, in the Financial Review section of the Annual Report for the year ended December 31, 2010, the CFO, Mr. Hussain, disclosed:

- “Close management of sales pipelines on a quarterly basis to improve visibility in results expectations”;

- “Annual and quarterly target setting to enable results achievement”;

- “Close monitoring by management of revenue and cost forecasts”;

- “Adjustment to expenditures in the event of anticipated revenue shortfalls”; and

- “Close monitoring of reseller sales cycles.”

The same Financial Review also disclosed (in case anyone might have been unaware of the fact) that late in-the-cycle purchasing was common in the software industry.

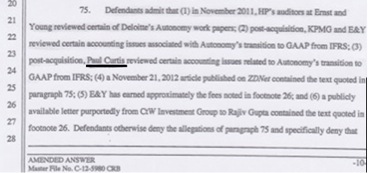

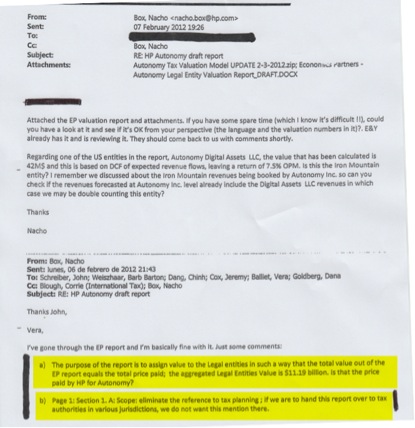

D. HP’s Own Experts Reviewed Autonomy’s Accounting and Raised No Concerns

Immediately after the Autonomy acquisition was finalized in October 2011, HP hired Ernst & Young (“E&Y“) to perform an independent review of Deloitte’s audit files on Autonomy. Those files included Deloitte’s quarterly reports to Autonomy’s Audit Committee, which described, among other things, Autonomy’s strategic sales of hardware and reseller transactions (discussed in more detail below). HP does not claim, and there is no indication anywhere in the available record, that E&Y identified any concerns or issues regarding Autonomy’s accounts or accounting policies. Rather, E&Y appeared to be comfortable with Autonomy’s accounting.

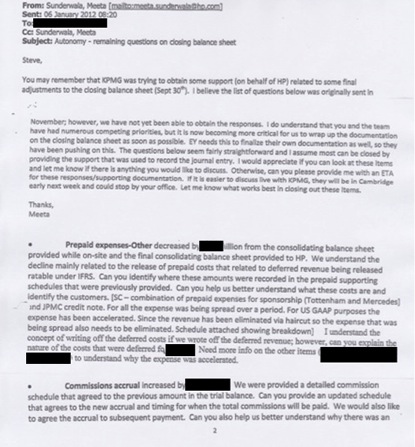

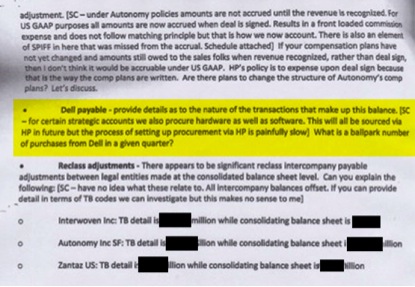

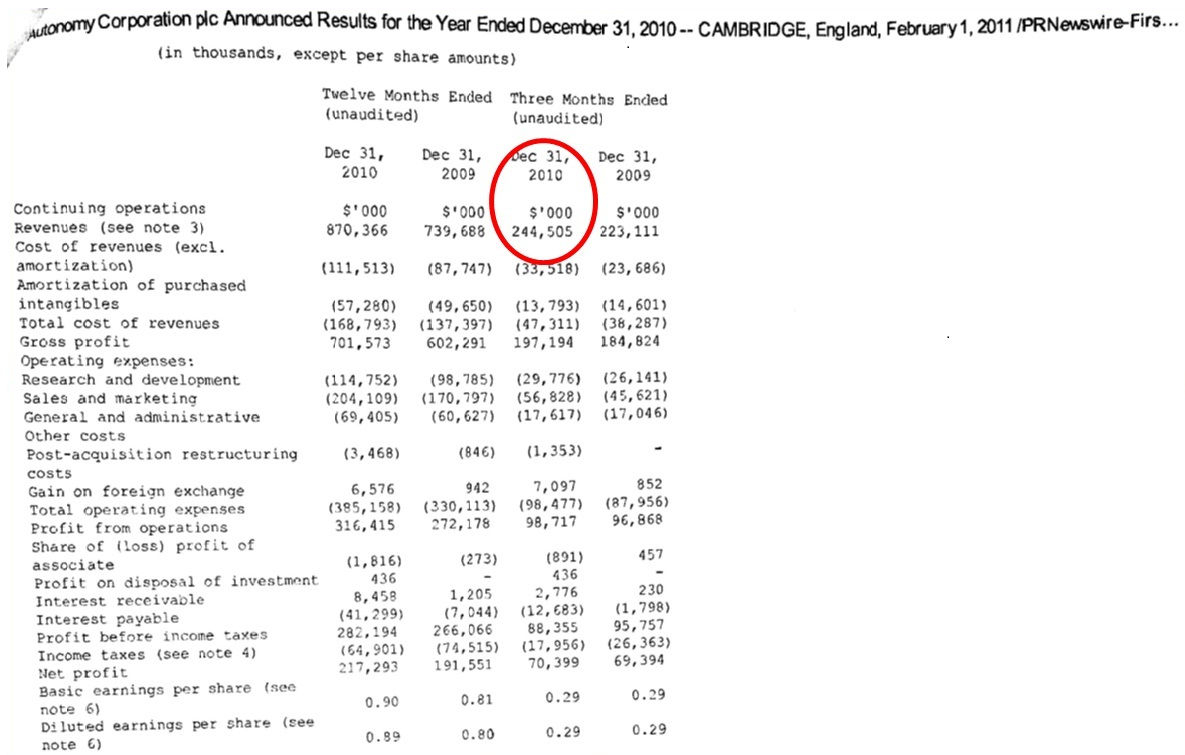

At around the same time, HP hired KPMG to review Autonomy’s opening balance sheet and past transactions. KPMG, too, expressed no concerns about the propriety of Autonomy’s accounts or policies, and appeared to be comfortable with Autonomy’s accounting. In fact, HP and its outside advisors reviewed Autonomy’s accounts thoroughly enough to determine that it would be acceptable to take a $45 million write-off and promptly did so, yet neither party found anything to suggest that there was any impropriety at Autonomy, let alone a massive fraud.

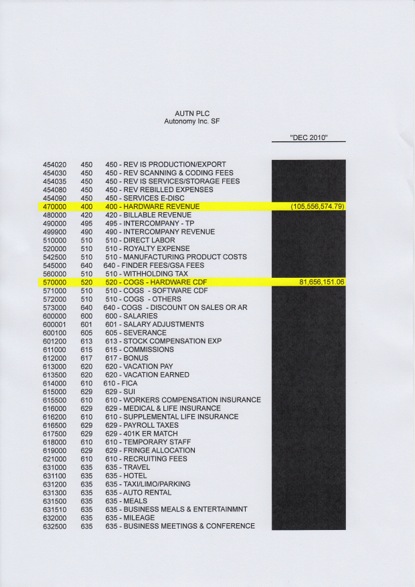

II. HARDWARE ALLEGATIONS

A. Background

Autonomy sold hardware to drive software sales. This perfectly legitimate practice was widely known, handled openly within the company, and carefully monitored and approved by Deloitte and the Audit Committee. In 2009, there were three significant developments in the market for Autonomy’s Digital Safe software:

(1) Shift to appliances: Many industry analysts were predicting that traditional sales of software would be replaced by the sale of software pre-loaded on hardware—what became known as an appliance. At around this time, Google developed a search appliance that directly competed with Autonomy’s software products, and Whit Andrews of Gartner, an influential industry analyst, actually de-rated Autonomy for its weakness in the appliance category. Autonomy was in a difficult position because it could not purchase hardware cheaply enough from manufacturers to produce a competitively priced appliance product or optimize appliance performance via customized hardware.

(2) Customers combining hardware and software on-site: Autonomy had been selling hosted Digital Safe archiving to banking customers. As these clients’ archiving needs exploded in an increasingly digital and regulated world, some customers decided to purchase both the software and the necessary hardware (though not necessarily at exactly the same time) and then put the two together on-site as needed.

(3) Strategic supplier status: By 2009, a number of large Autonomy customers were reviewing their IT supply chains to streamline the number of suppliers that they would deal with directly. The trend was to designate the largest vendors as “strategic suppliers,” who would in effect act as general contractors, procuring from smaller vendors whatever products they themselves did not make, and taking for themselves some of the profit on the resale. This shift jeopardized Autonomy’s access to such customers, because it did not sell them enough software to qualify as a strategic supplier. Unless Autonomy could find a way to significantly increase its aggregate sales to these clients, it would have to route its future sales through strategic suppliers, and would therefore have to dramatically reduce its margin in order to maintain an attractive price to the end user despite the intermediary’s markup (typically 30 percent). Or, worse yet, certain larger companies with strategic supplier status—such as EMC or IBM—could have decided to produce directly competing software products, potentially eliminating entire categories of key sales. To ensure strategic supplier status with such customers and thereby protect its software margins and sales opportunities, Autonomy thus sought to increase its aggregate sales volume by offering hardware.

As a result of these three market shifts, Autonomy sought to develop strategic relationships with hardware suppliers in order to: (1) obtain hardware in competitive volumes and at competitive prices and, through such marketing relationships, generate sales of that hardware to in turn generate sales of software; (2) develop relationships with hardware vendors that could help Autonomy find a solution to the strategic threat arising from the industry move toward appliances; and (3) develop relationships with hardware suppliers to foster joint marketing activities. In particular, Autonomy’s management made it a priority to develop closer relationships with key hardware suppliers EMC, Dell, and Hitachi. Autonomy fully disclosed this initiative, and the reasons behind it, to the Audit Committee and Deloitte. Autonomy’s internal Strategic Deals Memorandum, to which HP refers in paragraph 142.9.1 of the Particulars, sets out Autonomy’s rationale for selling hardware.

The strategy was successful: Autonomy entered into strategic hardware agreements in Q3 2009 with Citigroup, Bloomberg, and JPMC. Autonomy initially partnered with EMC to procure this hardware, but shortly after Autonomy began shipping EMC hardware under this arrangement, EMC’s content group acquired an Autonomy competitor, resulting in the termination of the hardware relationship. Autonomy continued to maintain a cordial relationship with EMC, however, and in 2010 Autonomy even considered acquiring EMC’s content division for approximately $2.4 billion. Although the deal fell apart when EMC’s content division repeatedly missed its numbers, the negotiations show that the relationship with EMC was a continuing and potentially beneficial one.

As its hardware relationship with EMC came to an end, Autonomy began to form a closer relationship with Dell, which was in any event better positioned to help Autonomy because Dell, unlike EMC, was able to supply servers as well as storage. As a result, Autonomy used Dell as its hardware supplier from the end of 2009 until 2011.

B. HP’s Baseless Allegations

HP has alleged three broad categories of accounting irregularities:

- Autonomy’s loss-making hardware sales;

- Autonomy’s accounting for hardware sales; and

- Autonomy’s disclosure of hardware sales.

None of HP’s allegations hold water.

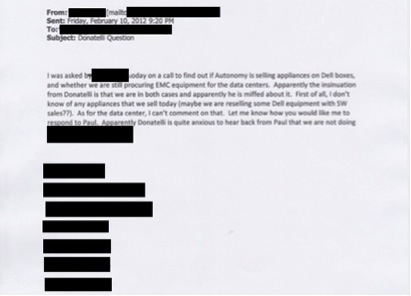

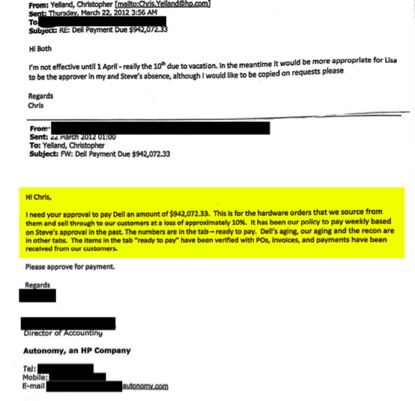

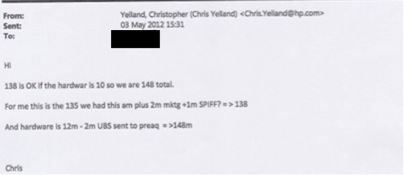

Indeed, HP seems to find its own arguments about hardware less than persuasive, given how many times it has changed its story since it began its public witch-hunt in 2012. First, HP claimed in its November 20, 2012, press release, and in an interview with Bloomberg the same day, that it had “no knowledge or visibility” of Autonomy’s hardware sales until May 2012. But HP has since had to admit that E&Y’s November 2011 review of Deloitte’s work papers “identified Autonomy’s hardware revenue, which E&Y reported to HP,” and that KPMG’s 2011 review likewise identified $41 million in Autonomy hardware sales, which “HP management” discussed with Autonomy at the time. Indeed, we are confident the evidence will show that not only did HP ask specific questions about Autonomy’s hardware sales, including questions about the type and amount of Dell hardware transactions, but also that Autonomy provided prompt, accurate, and complete responses to those questions. Unable to sustain its initial public claims of ignorance in the face of hard evidence to the contrary, HP then made a new allegation: that although it was aware of the fact and quantity of Autonomy’s hardware sales, it did not know what type of hardware Autonomy sold. But HP was soon forced to abandon this argument too; a September 12, 2014, Wall Street Journal article quoted an HP spokeswoman who admitted that in 2011 Autonomy “described [its hardware sales to HP] as either ‘appliance sales’ or ‘strategic sales’ designed to further purchases of Autonomy software.” Contemporaneous emails confirm this fact.

With its prior false claims about Autonomy’s hardware sales conclusively debunked, HP has retreated to vague and unsupportable generalities, asserting that it never knew that Autonomy sold “pure” hardware (whatever that means). What is clear, however, is that HP was well aware in 2011 that Autonomy sold hardware for the strategic purpose of driving its core software sales. HP nonetheless appears to imply (in paragraph 54 of the Particulars) that if hardware and software sales were not included on the same order, then there could be no link between the sales. This implication is utterly unfounded and flatly wrong. Strategic hardware sales were undertaken to promote not only present but also future software sales; thus, such sales could plainly be linked even though they took place at different times and therefore appeared on separate purchase orders. To use an analogy, on HP’s reasoning the sale of a video game system could not possibly be linked to the future sale of a game to be played on that system because the two sales would not be recorded on the same piece of paper. Such an argument is contrary to plain common sense (a problem that confronts all of HP’s allegations against Autonomy, as will be seen below).

Further evidence that the hardware and software sales were linked—if any further evidence were needed—comes in the form of HP’s own continued resales of Dell hardware to drive Autonomy software sales well into 2012, long after the acquisition was completed and HP’s finance team had taken control of Autonomy’s accounting. Senior HP accountants and advisors inquired about the Dell hardware resales and knew that they were made at a loss. Indeed, the available record suggests that these resales were ultimately terminated not by HP but by Dell.

HP’s numerical estimates of the revenue generated by what it calls “pure” hardware revenue are likewise far off the mark. Despite repeated requests, HP has failed to provide the documentation behind these figures, but from the available information HP appears to include in the category of so-called “pure” hardware revenue (a) profitable sales of hardware, (b) hardware sold with software, (c) hardware sold for combination with Autonomy software on the customer site as part of appliance programs, and (d) hardware sold under agreements where customers explicitly linked hardware and software purchases from Autonomy for calculations of overall discount targets. HP does not explain, of course, how such transactions can possibly be characterized as loss-making sales unconnected to profitable software sales (if, indeed, that is its intended meaning of “pure” hardware sales) and thus even on its own definition HP overestimates the percentages of revenue involved.

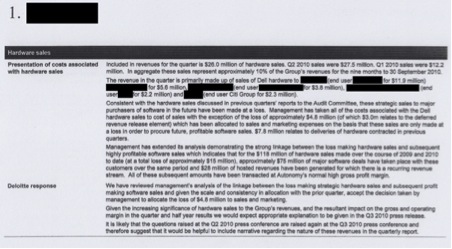

1. Autonomy Properly Accounted for Its Hardware Sales

Autonomy appropriately accounted for the costs associated with its strategic hardware sales. Contrary to HP’s assertion (in paragraphs 68.3 and 68.4 of the Particulars) that Autonomy improperly accounted for some of those costs as sales and marketing expenses rather than costs of goods sold (“COGS“), IFRS provides no accounting standard governing cost accounting for discounted strategic sales, or the extent to which such costs should be allocated between COGS and sales and marketing costs. Rather, this is an area reserved to the directors’ judgment, subject to the scrutiny of internal and external auditors. Autonomy’s allocation of these costs was at all times reviewed by its Audit Committee and Deloitte, who uniformly approved Autonomy’s accounts.

Under IAS 8.10, the objective of the cost allocation should be to reflect the underlying economic substance of the transaction. Accordingly, the appropriate test is whether and to what extent Autonomy’s strategic hardware sales were made for marketing purposes—i.e., to promote future software sales. Consistent with this principle, Autonomy estimated the COGS component of its hardware costs by looking to the standard cost of such hardware (as provided, for example, by EMC), and then categorized the remainder of its actual costs—i.e., the amount above the standard hardware cost, which could only be attributable to Autonomy’s strategic purpose in undertaking the sales—as a sales and marketing expense. This straightforward and common-sense approach follows the normal accounting and business methods for establishing the value of separate parts of a transaction and, again, was fully overseen by Deloitte, who satisfied itself that this accounting complied with IFRS.

HP’s allegations to the contrary are based on selective quotations taken out of context and mischaracterized. For example, paragraph 142.8.1 of the Particulars alleges that Mr. Hussain misrepresented to the Audit Committee in Q3 2009 that Autonomy and EMC were engaged in a “highly targeted joint marketing program” and that Autonomy had “spent US$20 million on shared marketing costs with EMC” when, in reality, neither the joint marketing program nor the shared marketing expenditure existed. The full quotation from the note reveals, however, that Mr. Hussain was accurately describing movement in quarterly operating costs: “There were 2 large movements. Firstly, in sales and marketing we spent around $20m on sharing marketing costs with EMC and extra marketing on our new product launch (Structured Probabilistic Engine).”

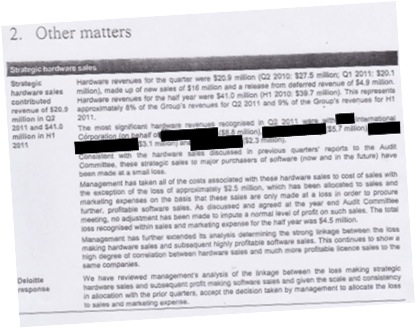

Similarly, in paragraph 142.8.3 of the Particulars, HP provides a misleading selective quotation in support of its claim that Mr. Hussain misrepresented to the Audit Committee in Q2 and Q3 2010 that the costs of hardware had been charged to COGS when, in fact, a portion of those costs had been charged to sales and marketing expenses. Mr. Hussain’s actual statement, however, was critically different from HP’s portrayal: “We have charged the cost of the lower margin sales to the cost of sales line even though we had agreed with our suppliers that the [sic] 50% of the cost would be used for marketing purposes.” This sentence conveyed that costs equal to the amount of the sales were allocated to COGS and the loss on the sales was allocated to the sales and marketing line. Deloitte made this clear in its report:

Management has taken all of the costs associated with the Dell hardware sales to cost of sales with the exception of the loss of approximately $3.8 million which has been allocated to sales and marketing expenses. . . . We have reviewed management’s analysis of the linkage between the loss making strategic hardware sales and subsequent profit making software sales and accept the decision of management to allocate the loss of $3.8 million to sales and marketing.

Finally, Autonomy’s marketing-cost allocation did not mislead the market by distorting its gross margins. The prosaic reality is that the gross-profit metric fluctuated in any event, and any impact of the hardware accounting was insignificant and consistent with the usual variations in this margin, which were highlighted in various analyst calls. In this context, the argument that a variation of a few percentage points in gross margin would have materially affected investors’ views of the company is patently false. Additionally, HP was aware of Autonomy’s hardware accounting immediately following the acquisition, if not sooner, yet made no indication that the accounting was problematic until over one year later.

In short, Autonomy’s hardware resales were precisely targeted, properly accounted for, fully explained to its internal and external auditors, and did not distort either the market’s assessment of Autonomy’s value or HP’s valuation of the company. Contrary to HP’s baseless accusation in paragraph 142.4 of the Particulars, Autonomy was not acting as a generic hardware reseller such as Morse. Autonomy’s hardware sales, typically made at a loss and always designed to benefit the software business, were plainly dissimilar to the business of a generic reseller of hardware.

2. Autonomy Fully Complied with Its Disclosure Obligations

As HP implicitly concedes in paragraph 30.1 of the Particulars, Autonomy acted in full compliance with IFRS in classifying the income generated by its hardware sales as revenue. There is no proper basis for deducting the hardware transactions from Autonomy’s revenue figures. The hardware transactions took place, hardware was delivered, and revenue and cash were generated in return.

IAS 18 requires disclosure of each significant category of revenue, with significance to be determined as a matter of judgment. Here, Autonomy’s highly qualified accounting executives determined that its hardware sales did not constitute a significant category of revenue for the purposes of IAS 18, and the Audit Committee and Deloitte concurred in the reasonableness of that judgment. Indeed, that judgment was not only reasonable but also patently correct. The discounted hardware sales were merely ancillary to Autonomy’s software sales, and the overall effect was a high-margin software business.

Under IFRS 8, the revenue stream from any particular component of sales should be separately disclosed where two criteria are met:

(a) The component qualifies as an “operating segment” under IFRS 8.5 to 8.10; and

(b) The revenue stream from that component meets the quantitative threshold established by IFRS 8.13.

An operating segment, as defined by IFRS 8.5–8.10, is a corporate component:

(a) That engages in business activities, and may thereby earn revenues and incur expenses;

(b) That has operating results that are regularly reviewed by the chief corporate decision maker; and

(c) For which discrete financial information is available.

A corporate activity whose revenues “are only incidental” to the corporation’s business is not an operating segment.

Autonomy properly applied these principles. Its hardware sales did not qualify as an operating segment because:

(a) Autonomy did not operate a separate hardware sales division;

(b) Hardware sales were not subject to separate review by Dr. Lynch; and

(c) Autonomy’s hardware sales were incidental and made primarily to drive the core software business.

As a result, Autonomy had no obligation to separately disclose its hardware sales under this guidance. Autonomy’s single-segment disclosure was reviewed by its Audit Committee and by Deloitte, who concurred with management’s decision to disclose Autonomy’s revenues as a single segment and properly found that Autonomy’s hardware sales disclosure was consistent with its accounts.

Nor did Autonomy mislead the market by stating that it was a “pure software” company, despite HP’s incessant allegations to the contrary. Indeed, that argument is not only false but also utterly disingenuous: HP is (and was) well aware that the term “pure software” did not signify that Autonomy did not sell hardware, nor did the market ever interpret it to mean any such thing. Autonomy used the term merely to distinguish itself from other software companies that derive a significant portion of their revenue from the provision of professional services, including consultancy.

Autonomy’s business model focused on developing and licensing IDOL software. The company was not designed to be a professional services provider; rather, its model depended on the existence of a community of expert systems integrators and consultants who could customize and implement the relevant IDOL software for each customer’s particular uses. This meaning was clear not only from the very statements of which HP complains, which drew explicit distinctions between Autonomy’s “pure software” approach and the services component of similar companies, but also from the many public sources of information disclosing that Autonomy sold hardware.

Indeed, it is self-evident that software needs hardware to work and, as a result, it is quite common for enterprise software companies to sell some hardware as an essential adjunct to the core business of promoting and procuring software sales. Thus, it simply is not plausible that a prospective buyer that knew anything at all about the software industry could have thought that the words “pure software” meant that Autonomy sold no hardware at all. And, perhaps most tellingly, investment bank analysts’ notes, which HP actually reviewed during its pre-acquisition valuation of Autonomy, made clear that the market understood the term “pure software” to relate to a professional services-lite operation, not an absence of hardware.

In conclusion, Autonomy did nothing wrong in selling hardware, appropriately accounted for its hardware sales in accordance with IFRS, and sufficiently disclosed its hardware sales to its auditors and to the market. Further, the evidence will show that HP was aware of Autonomy’s hardware sales prior to the acquisition and that HP continued to resell Dell hardware post-acquisition. In these circumstances, HP’s allegations of fraud are transparently meritless.

III. RESELLER ALLEGATIONS

A. Reseller Sales are Commonplace and Commercially Sound

Unsurprisingly, as group CEO, Dr. Lynch had little involvement in negotiating reseller deals or determining the related accounting. As a major player in the industry, however, Dr. Lynch was generally aware of the benefits of reseller deals and the importance of developing a reseller ecosystem.

In common with most software companies, including HP, Autonomy sought to develop and strengthen its reseller ecosystem, and thus often sold through reseller partners. Both Autonomy and the resellers derived commercial benefits from this arrangement. For Autonomy, these sales helped expand the network of providers that understood, marketed, and serviced Autonomy products. Through repeat business, resellers developed a deep understanding of Autonomy products, which enabled them to provide services and support to Autonomy’s customers (lower-margin tasks that Autonomy had little interest in performing itself). Additionally, certain resellers held GSA pricing schedules and/or government and security clearances beyond those held by Autonomy’s own employees. In partnering with these resellers, Autonomy gained access to markets it had not already penetrated. Under IFRS, a reseller was itself Autonomy’s customer for accounting purposes, and thus selling to the reseller amounted to a valid and enforceable sale.

Contrary to paragraph 74.3.6 of the Particulars, resellers could derive numerous commercial benefits from these sales. Such deals gave resellers the opportunity to connect with a new customer, gain a new reference logo, provide services, lock out competitors, and simply make sales and margin. And even where there was an intended end user of the product, the reseller could always negotiate with and sell to a different end user if it thought it could get more favorable terms.

As one means to foster these relationships, Autonomy would occasionally pay a marketing assistance fee (“MAF“) to compensate a reseller for its assistance in a sale or to make up for its lost margin where an end user ultimately elected to purchase directly from Autonomy. Autonomy took such steps voluntarily and in its discretion after a sale was completed. In each instance, such steps advanced Autonomy’s valid commercial interests in the success of its partners, the sale of its products to interested customers, and the related development of an ecosystem around its products. Deloitte reviewed and approved Autonomy’s use of MAFs, and openly discussed them in the Reports to the Audit Committee.

HP’s feigned surprise at finding that Autonomy engaged in reseller deals is especially disingenuous in light of the fact that HP operates a number of its own reseller compensation programs—ranging from opaque “contra” transactions to programs in which an HP reseller is entitled to rebates and referral fees for sales by HP where the partner somehow influenced the sales process. HP’s Reseller PartnerOne EMEA Program Guide, dated November 2012, explains that the PartnerOne program compensates reseller partners for, among other things, referrals: “A referral is when a customer buys directly from HP and the partner has been recognized for their contribution to the closing of that deal via a referral fee.” The guide goes on to list a few examples of such compensable contributions: “Referral fees are discretionary payments made to non-reselling partners, where the partner had demonstrable influence on a deal made directly between HP Software and the customer. Demonstrable influence can refer to: identification of sales opportunity, recommendation of the HP solution, involvement in the sales cycle, proof of concept, solution architecture, or associated return on investment.“

Notwithstanding the frequency of these relationships in the software industry and the well-understood benefits of developing a reseller ecosystem, HP suggests that Autonomy was somehow unique in developing this ecosystem and attempted to conceal its relationships with resellers. Contrary to paragraph 136.5.1 of the Particulars, the fact that Autonomy partnered with resellers was transparent and any decline in Autonomy’s use of resellers after the acquisition was primarily due to HP’s desire to funnel business to its own services arm, HP Enterprise Services.

B. HP Fundamentally Misunderstands the Relevant Accounting Principles

HP’s allegations regarding reseller transactions are based on its fundamental misunderstanding of IAS 18, Autonomy’s accounting policy, and the nature of the reseller transactions themselves, all of which were legitimate and appropriately accounted for under IFRS. Further, it should be noted that HP singles out only a handful of individual transactions, making the baseless assertion that the resellers were not on risk for those transactions (despite the voluminous documentary evidence making clear that they were), and then desperately tries to extrapolate from these deals to the 23,000 reseller transactions that Autonomy conducted in the relevant period.

HP’s first, and most basic, error is its failure to comprehend that for accounting purposes it is the reseller, not any intended end user, that is Autonomy’s customer. Cathie Lesjak, HP’s CFO, misunderstood this as long ago as November 2012, and HP apparently has never regained its wits on the issue. The naming of an intended end user in the sales documentation with a reseller, although helpful to Autonomy in its management of the business, is not and never was a requirement under IFRS.

HP also misunderstands the concept of “risk” under IAS 18. HP’s allegation that resellers were not “on risk” when Autonomy recognized revenue on its sales to them is unsupported by the evidence and, indeed, flies in the face of the resellers’ repeated and well-documented acknowledgments—in response to inquiries by Deloitte—that they were indeed on risk. Nor was there any pattern of returns or cancellations sufficient to cast doubt on the propriety of revenue recognition upon a sale to any reseller. Deloitte actively reviewed reseller transactions, was alive to the issue of risk transference, and, in each case, approved Autonomy’s accounts.

Consistent with IFRS and IAS 18, Autonomy’s revenue-recognition policy provided for recognition of revenue on sales of IDOL product to resellers when the software licenses at issue had been “delivered in the current period, no right of return policy exist[ed], collection [wa]s probable and the fee [wa]s fixed and determinable.” Autonomy’s policy was approved by Deloitte and the Audit Committee, disclosed in Autonomy’s annual report, and led to the appropriate recognition of revenue under the five-element IAS 18 test:

(1) Autonomy transferred the significant risks and rewards of software ownership to each reseller upon executing a purchase order and delivering the software.

(2) Autonomy did not retain continuing managerial involvement to the degree usually associated with ownership or effective control over the goods sold. The reseller had ultimate control over any resale.

(3) Autonomy’s sales to resellers were fixed with regard to price at the time of sale and were not contingent upon future events. As a result, Autonomy was able to reliably measure revenue at the time of each sale.

(4) Autonomy recognized revenue on a sale to a reseller only where it was probable—i.e., more likely than not—that Autonomy would be paid by the reseller. Autonomy assessed collectability according to a number of criteria, including the reseller’s creditworthiness based on third-party credit reports, payment history, and the strength of the reseller’s balance sheet.

(5) Autonomy maintained records of all sales and, as a result, reliably measured costs.

1. Transfer of Risks and Rewards

Autonomy transferred the significant risks and rewards of software ownership to each reseller when the contract was executed and the software was made available for delivery. Autonomy transacted with resellers pursuant to non-recourse agreements, under which neither the fixed price for a license nor the obligation to pay was contingent on a reseller’s eventual resale of the license to an end user. As a result, each reseller assumed the risk of not reselling the software to an end user. As a further precaution, it was Deloitte’s policy to obtain written revenue confirmation directly from each reseller before approving Autonomy’s recognition of revenue for deals over $1 million. Those letters confirmed that the resellers were on risk and that no side agreements, written or oral, were in place.

2. Continuing Managerial Involvement

Autonomy did not retain continuing managerial involvement to the degree usually associated with ownership or effective control over the goods sold. Any post-sale involvement by Autonomy did not amount to the type consistent with ownership or control that IAS 18.14 contemplates. Contrary to HP’s insinuations, IFRS does not prohibit contact with an end user after a sale to a reseller; rather, it is not only permitted but also commonplace for software companies to maintain contact with an end user following a sale to a reseller. For example, a reseller may rely on the software company to act as its negotiating agent; a transaction with a reseller may be only one part of a larger contemplated deal; or a software company may have a long-standing relationship with an end user that is important to maintain.

Contrary to HP’s statement in paragraph 74.3.3 of the Particulars, IFRS does not require a reseller to add value in connection with a specific sale to an end user in order for the revenue on the manufacturer’s sale to that reseller to be recognizable. Under IAS 18.14(b), in order to recognize revenue on a sale, a seller may retain neither “continuing managerial involvement to the degree usually associated with ownership nor effective control over the goods sold.” HP appears to assert that resellers lacked active participation in end-user negotiations following a purchase from Autonomy and that this undermines Autonomy’s satisfaction of this element of the test. It does not. Simply stated, there is no requirement under IFRS that a reseller initiate or take the lead in negotiations on an onward sale to an end user, or otherwise add value to the particular product sold, before revenue can be recognized on the transaction between the seller and the reseller.

The relevant consideration under IAS 18.14(b) is not whether the reseller participates in negotiations with the ultimate end user, but whether the logistics of the resale are within the seller’s ultimate control and whether the seller is responsible for the management of the goods after the sale. Here, Autonomy lacked, and the resellers possessed, control over both the decision to whom and whether the reseller sold the software, and management of the software following the reseller’s purchase. Both features demonstrate that Autonomy relinquished managerial involvement and effective control to the resellers that were its customers.

3. Fixed Price Not Contingent on Future Events

On infrequent occasions, a reseller’s contemplated onward resale to an end user fell through, either because no end user purchased the software at all, because Autonomy entered into a direct transaction with the anticipated end user, or because the reseller decided to sell to another reseller instead of the originally contemplated end user. Those subsequent events did not, however, undermine the appropriateness of Autonomy’s recognition of revenue at the time of sale to the reseller. Accounting judgments are not made with hindsight. Simply put, a change in circumstances that occurs after a sale, which was not contemplated at the time of the transaction, does not undermine the initial recognition decision. Additionally, Deloitte carefully tracked reseller sales across quarters and clearly understood the fate of these deals.

While, at times, resellers used the failure of an onward resale to try to excuse nonpayment to Autonomy or to negotiate extended payment terms, these unremarkable commercial tactics did not affect a reseller’s obligation to pay or the propriety of Autonomy’s recognition of revenue at the time of the sale to the reseller. Deloitte was aware of these issues and tracked and considered reseller payment histories when assessing the propriety of revenue recognition. For example, the Report to the Audit Committee on the Q1 2010 Review stated:

Management alerted us to the fact that two deals sold to Microtech in Q4 2009 have been credited in this quarter and resold directly to the two end users. This was as a result of the end users wanting to transact directly with Autonomy. This reduced the profit in the period by approximately $4 million. As there is no significant history of deals being reversed in this way, management has recognised the revenue at the point of sale to the reseller. Management has confirmed that these were isolated incidents which are not expected to be repeated in future periods.

On the limited occasions when a reseller deal was cancelled or debt forgiven, Autonomy granted the relevant concession as a business decision and not because this was expected at the outset. Moreover, such rare events in the audited period were known to Deloitte, who ensured that the related accounting treatment was appropriate.

4. Probability of Payment and Records of Cash Received

Cash for reseller deals was nearly always received, and the cancellation rate on contracts was low. In its purported restatement of the Autonomy accounts, HP appears to indicate that a significant number of these sales should never have been booked at all, despite the fact that the bulk of the cash was actually received. On the currently available information, out of revenues in the period of around $2.3 billion, HP has removed $140 million of revenue from reseller deals. However, HP itself concedes that cash of $102 million was received against this revenue. HP makes no explanation regarding where this now-surplus cash came from.

C. Specific Deals

While each deal was different and each reseller and end user unique, the following discussion addresses a few of the many glaring deficiencies in HP’s allegations, which highlight HP’s incorrect application of IFRS.

1. Capax (End User Kraft)

Capax was a key part of the Autonomy ecosystem, and HP still considers it a major HP Autonomy partner to this day. Deloitte was comfortable with Autonomy’s revenue recognition on sales to Capax, as discussed below. Moreover, in 2011, the FRRP considered Capax’s ability to stand by its obligations to Autonomy and concluded as follows, in a letter dated August 22, 2011: “The Panel notes that [Autonomy] started to do business with Capax in early 2009 and that Capax has had an excellent payment record since then. . . . The Panel notes that [Capax's accounts] show Capax to be solvent at 31 December 2008 and to have traded profitably in the year then ended.”

In Q3 2009, Autonomy executed a $4 million deal with Capax for end user Kraft. It is plain that Autonomy’s accounting treatment of this sale was in accordance with IFRS and approved by Deloitte, as demonstrated by the Report to the Audit Committee on the Q3 2009 Review:

Kraft Food Inc (“Kraft”)

This is a $4 million licence deal for a suite of Autonomy software including Zantaz Digital Safe, Aungate and Introspect. Support and maintenance has been charged at $0.2 million which is consistent with fair value on a deal of this size. It should be noted that this deal has been signed through the reseller, Capax Discovery LLP (“Capax”). As Capax are up-to-date with their payment terms with Autonomy, and all other revenue recognition criteria have been met, management has concluded it is appropriate to recognise revenue.

In Q4 2009, for reasons unforeseen at the time of the reseller deal, Autonomy closed a direct deal with Kraft. Thereafter, Autonomy, in an exercise of its discretion and for sound commercial reasons, cancelled the reseller deal and offered Capax compensation for its earlier assistance. HP’s allegations about the Kraft transaction were investigated and dismissed by the FRRP, which in 2011 considered Kraft’s decision to seek a direct agreement with Autonomy and concluded that “Kraft may have felt more comfortable dealing with the key supplier which was also a global company able to provide 24 hour support worldwide.” The FRRP also understood the reasons why Autonomy paid a MAF to Capax on this deal. The FRRP dismissed the allegations concerning the Kraft transaction and declined to pursue the matter further. Having been reviewed and approved by Deloitte, the Audit Committee, and the FRRP, it is clear that the accounting for the deal was proper, despite HP’s desperate attempts to claim otherwise.

2. MicroTech (Intended End User the Vatican)

HP alleges in paragraph 78 of the Particulars that Autonomy’s sale of software to MicroTech, with the Vatican as the intended end user, lacked commercial purpose. HP is wrong. From approximately 2008/2009 to 2012, Autonomy and the Vatican negotiated a deal to digitize the Vatican Library’s collection of 80,000 manuscripts. Autonomy and the Vatican worked together over many months to develop a full test bed system in Vatican City. This system was the subject of television interviews, and the Vatican issued press releases about the project. In November 2009, Mr. Hussain presented the deal to Autonomy’s board for approval. At the time, Autonomy was to receive €75 million over ten years from the deal, which would be not only lucrative but also high-profile and likely to draw market interest to Autonomy’s cutting-edge solutions.

On March 31, 2010, as negotiations continued, Autonomy sold MicroTech $11.55 million of software to be resold to the Vatican as part of the larger Autonomy/Vatican deal. Autonomy wanted to involve a partner with sufficient Autonomy expertise to write application code. Other partners would in time be required in Italy to help with installation. The auditors were familiar with the MicroTech/Vatican deal, which was discussed and examined during the Q1 2010 review, and confirmed that the accounting was proper.

Negotiations with the Vatican continued into 2012, but HP ultimately decided not to pursue the deal, apparently ceding at least part of it to EMC. The Financial Times reported on January 23, 2015, that the digitization of the Vatican Library was about to take place with NTT DATA as the service provider. In short, it is clear that the Vatican deal was a real opportunity and not, as HP insinuates, a pretext for Autonomy to recognize phantom revenue. Indeed, there is every reason to believe that Autonomy would ultimately have secured the deal for itself had HP not abandoned the negotiations.

The MicroTech deal satisfied all of the revenue-recognition tests under IFRS. MicroTech was on risk for the balance of its debt, regardless of whether a deal closed with the Vatican. Autonomy did not retain effective control over the goods sold. And, indeed, MicroTech made payments in Q4 2010 and Q2 2011 to reduce the Vatican balance that it owed to Autonomy, paying off all but $2.3 million of its $11.55 million balance on the deal prior to the acquisition. HP then wrote off the remaining $2.3 million despite the fact that negotiations with the Vatican were still ongoing at the time.

3. FileTek (Intended End User the VA)

Contrary to HP’s claim in paragraph 91.1 of the Particulars, FileTek had been reselling Autonomy technology for over a year before the Department of Veterans Affairs (“VA“) transaction of which HP complains. Likewise, Autonomy had been working with the VA for some time. When this particular deal was first considered, evidence was mounting that the VA would be issuing a request for information (“RFI“) with a value of tens of millions of dollars, and that Autonomy was likely to be the chosen technology (since, as mentioned above, the VA was an existing Autonomy customer).

In such situations, there are multiple ways in which a manufacturer or reseller could seek to participate in a sale. First, the reseller could respond to the expected RFI. Second, the reseller could supply the likely bidder or bidders for the RFI. Third, the reseller could sell a stopgap solution directly to the customer, if issuance of the RFI was delayed.

It is unsurprising that Autonomy and FileTek decided to partner on the VA deal, given that FileTek was involved in archiving structured data and was keen to get into the much higher growth area of unstructured data archiving offered by Autonomy. Additionally, Autonomy was a logical partner given the likelihood that Autonomy would be involved in the VA deal, however it was structured. The VA purchase order from FileTek reflects this, stating that the software could be licensed “either directly by [FileTek] or through an agreed to prime contractor to the United States Veterans Administration Authority (the ‘VA’) or to a Alternate Licensee.” FileTek could therefore sell the software to anyone, not just the VA. For example, FileTek could sell the software to a bidder on the VA deal, or as a stopgap to the VA, or to any other party or reseller not related to the VA. It thus appears to have made commercial sense for FileTek to enter into the deal, and FileTek paid Autonomy fully for the deal.

IV. ALLEGATIONS REGARDING PURCHASES FROM CUSTOMERS

As a matter of common sense, where partners had invested in creating an Autonomy-related business by, for example, building their capacity and knowledge with respect to a particular Autonomy product, it was in Autonomy’s commercial interest to support them in that endeavor by assisting them with implementation, funneling business in their direction, or using them as vendors when Autonomy had a particular need. Where Autonomy made purchases from its customers, it was appropriate under IFRS to account for those purchases in the same way as any other purchase so long as the exchange involved “dissimilar goods,” had “commercial substance,” and the “fair value” of the goods could be measured reliably.

Nonetheless, HP alleges that Autonomy engaged in so-called “reciprocal” purchases, and seeks to improperly remove large swaths of revenue generated by legitimate transactions by “netting” them against distinct sales of dissimilar goods to the same customers. This approach is not only incorrect as a factual matter but also betrays, once again, a fundamental misapprehension of the relevant accounting rules.

Contrary to HP’s claims in paragraph 74.4.3.3 of the Particulars, the theory that Autonomy made purchases to provide customers with cash to pay debts on previous deals fails for four key reasons:

(a) Fair value on each purchase was proved at the time, and in some cases Autonomy sold the acquired item on at a profit;

(b) The resellers often used the cash paid by Autonomy to provide services, and this is well documented;

(c) To net revenue on such transactions would misstate the accounts; and

(d) HP cannot explain why Autonomy would have spent cash on products of no value to it when it would have been much simpler and far more cost-effective to simply introduce the reseller to a new end-user customer for its Autonomy software, which would have been appropriate under IFRS.

The purchases at issue had commercial substance and fair value. IAS 18.10 provides that “[t]he amount of revenue arising on a transaction is usually determined by agreement between the entity and the buyer or user of the asset. It is measured at the fair value of the consideration received or receivable taking into account the amount of any trade discounts and volume rebates allowed by the entity.” Consistent with this rule, when Autonomy entered “exchange transactions,” the related revenue recorded was “measured at the fair value of the goods or services received.”

Autonomy provided its auditors, and Deloitte carefully evaluated, evidence supporting the “fair value” of the goods that Autonomy purchased from its customers. Autonomy normally obtained such evidence by gathering quotes from parties selling competing products. Deloitte considered this information, in conjunction with signed purchase orders, before confirming that fair value had been appropriately established. There can be no question that Deloitte was careful and thorough in its evaluation of these transactions. For example, in assessing Autonomy’s purchase of FileTek software, StorHouse, in Q4 2009, Deloitte went so far as to bring in its own IT people in order to understand the commercial rationale for the purchase.

Further, the instances cited by HP include sale and purchase transactions with the same customer where cash was received and paid. As stated in paragraphs 10 and 11 of IAS 18, “[t]he amount of revenue arising on a transaction is . . . . measured at the fair value of the consideration received or receivable . . . . [and in] most cases . . . is the amount of cash or cash equivalents received or receivable.” In HP’s recent filings in the UK Action, for each of the allegedly reciprocal purchases that involved cash consideration, both the revenue and costs recorded by Autonomy reflected the fair value of the relevant products sold and purchased. Examples of these are addressed below in more detail.

HP’s claim that buy and sell transactions with the same counterparty should be netted against each other is incorrect; under paragraph 12 of IAS 18, dissimilar goods cannot be netted and exchange transactions involving similar goods also are not netted; rather, under paragraph 12 the latter are treated as generating no revenue at all, and thus there is nothing to be netted.

A. Specific Deals

1. The MicroTech ATIC

Throughout 2009 and 2010, Autonomy made strides to grow its federal business. With this objective in mind, it set ambitious growth targets for 2011. In order to secure federal contracts, however, Autonomy needed a space that complied with federal clearance requirements in which to demonstrate its capabilities to federal customers. As a possible solution, Autonomy considered partnering with a federally cleared entity.

In November 2010, MicroTech proposed building a federally cleared facility—the Advanced Technology Innovation Center (“ATIC“)—in which to showcase Autonomy solutions to federal customers. MicroTech proposed to both market existing solutions and help Autonomy develop and test new solutions. To do so, MicroTech needed to hire a full-time federally cleared staff, lease a sufficiently large office space, and acquire the necessary technology—and much of this cost would be incurred up front. In light of the substantial investment and construction involved, it was always understood that the facility would not be available until sometime in 2011.

The parties entered into negotiations on the deal on the basis of a comprehensive document. On December 30, 2010, after negotiating price and license terms, including a discount of almost 17 percent for early payment, Autonomy purchased a three-year license for the ATIC. Autonomy paid MicroTech $9.6 million for the license the following day.

Mindful of the fact that MicroTech was a repeat Autonomy partner, Deloitte reviewed the transaction, confirmed that Autonomy paid fair value, and approved the accounting. Specifically, the Report to the Audit Committee on the Q4 2010 Review stated:

In December 2010 a licence was purchased by Autonomy from Microtech for $9.6 million and capitalised on the balance sheet as an intangible asset. This relates to a 3 year license to use a fully US federal government certified demonstration facility which will remain the property of Microtech throughout the licence term. The licence will include six dedicated US federal cleared employees of Microtech who each have many years of experience in dealing with US federal government sales. We understand that these individuals have significant business connections with US federal organisation[s].

Given that Microtech is a regular customer of Autonomy, we have reviewed this transaction to ensure that it makes commercial sense and that there is no indication that this should be considered a barter transaction. . . . We held discussions with Sushovan Hussain and Dr Pete Menell who explained that at present Autonomy struggle[s] to make significant sales into the US Federal government agencies because they do not have the appropriate level of certification.

In June 2011, the ATIC was launched with much marketing fanfare and was made available for Autonomy’s use. Contrary to HP’s claim in paragraph 78.7 of the Particulars, the ATIC was hardly a van (and the fact that HP is making such an assertion after two and a half years of “investigation” is simply astonishing). Rather, the facility included a MicroData Center; Emerging Technologies Center; Test, Evaluation, and Integration Lab; and Mobile data center (which could be used to offer demonstrations to customers off site). These components were specified in a thirty-page document. Because the ATIC was launched in June 2011, however, Autonomy had few opportunities to utilize the facility before being acquired by HP. Following the Autonomy acquisition, HP decided not to use the ATIC after all, and wrote the asset off without informing Autonomy management. HP then introduced a new method of managing federal customers.

2. FileTek StorHouse

HP claims, in yet another misguided attempt to find some justification for the write-down, that Autonomy’s purchases of FileTek’s StorHouse software in Q4 2009 and Q2 2010 were reciprocal transactions and valueless to Autonomy. Even further, HP claims that StorHouse was never successfully integrated with Autonomy’s software, used by the company, or sold on to a third party—all in the face of significant documentary evidence to the contrary (which would have been revealed by even a cursory review of the purchase orders to which HP had full access following the acquisition).

By way of background, Autonomy had established itself as an industry leader in unstructured information, but it had long been a strategic goal to combine that capability with structured data power. In fact, the prospect of creating a unique combined solution was a key motivating factor in HP’s subsequent acquisition of Autonomy. As part of that goal, Autonomy purchased FileTek’s StorHouse software in Q4 2009 and Q2 2010.

Deloitte undertook a comprehensive review of the purchase, with the help of its own IT specialist. Contrary to the statements in paragraphs 88.4 and 146.1 of the Particulars, Deloitte reported the following in the Report to the Audit Committee on the Q4 2009 Review:

We have reviewed the accounting for sale to and the purchase from Filetek. In addition to our standard procedures when auditing revenues, we involved a member of our IT specialists to ensure that the software purchased made commercial sense and was not in any way linked to the sale of Autonomy product to Filetek. We have sighted management’s work on confirming the fair value of this purchase and concur with the accounting treatment applied to the purchase and the sale to Filetek.

As part of the Q4 2010 Review, Deloitte also confirmed that Autonomy paid fair value for the purchase and that the accounting treatment was appropriate.

Deloitte’s statements regarding the demonstration in January 2010 are in direct contradiction to HP’s assertions in paragraph 88.4 of the Particulars that Autonomy did not download the software until April 2010. In fact, shortly after the purchase, engineers in both the United Kingdom and the United States undertook serious and substantial efforts to integrate the FileTek software, in consultation with FileTek’s own team. Autonomy ultimately considered four options for integration and chose the most technically complex and ambitious of these options, which, according to Autonomy engineers, provided the best offering to the customer and used both systems to their full potential. It did so by permitting Autonomy’s software to directly access data from a structured database.

By June 2010, Autonomy engineers confirmed that the FileTek software had been successfully integrated into its Digital Safe platform, with Autonomy presenting an integrated offering to Kraft. Autonomy’s successful integration of FileTek is reflected in: (1) the Report to the Audit Committee on the Q2 2010 Review, which specifically notes Autonomy’s success with Kraft; and (2) subsequent Autonomy contracts, which list FileTek software as part of the Digital Safe 9.0 platform. In July 2010, Autonomy conducted an additional technical demonstration for Deloitte. That demonstration is noted in the Report to the Audit Committee.

Over the next year, Autonomy made a number of significant sales of Digital Safe with integrated FileTek technology, and expanded its use of FileTek software with its archiving product LiveVault and in connection with newly acquired Iron Mountain data centers in the United States and the United Kingdom. Autonomy’s integration of FileTek software into its Iron Mountain data centers, and its use of the software, is well documented. For example, in August 2011, Autonomy circulated a list of its offices and sites that were using FileTek software.

In conclusion, Autonomy’s purchases of FileTek software were consistent with its strategy for entering the structured-data market, acquired at fair value, successfully integrated into Autonomy software, and sold to third parties. The transactions were reviewed by the Audit Committee and Deloitte, and also by the FRRP, and consistently found to be proper.

3. VMS

At paragraph 85.3 of the Particulars, HP entirely mischaracterizes the context in which Autonomy acquired data feeds from Video Monitoring Services (“VMS“). Prior to the VMS transaction, Moreover Technologies Inc. (“Moreover“), then a young company, used Autonomy technology, and in consideration provided Autonomy with news data feeds at no charge, which Autonomy in turn used to demonstrate its own technology. At around the time of the VMS deal, however, Moreover informed Autonomy that it had begun to use an Autonomy competitor’s technology and would no longer supply Autonomy with free data feeds. Thus, Autonomy sought an alternative source for such data feeds, considered quotes from several suppliers, and ultimately executed a deal with VMS.

It appears that HP’s real reason for proposing that these sales be reversed is not that they were part of “reciprocal” transactions, but that HP ultimately wrote off the related receivable balances because VMS went bankrupt in the second half of 2011. Where no cash is ultimately received on a transaction because a reseller’s financial position has deteriorated significantly, this can give rise to a bad-debt provision in accordance with IAS 18 but does not affect the appropriateness of the original revenue recognition by the seller. If “an uncertainty arises about the collectability of an amount already included in revenue,” IAS 18 (paragraph 18) requires that “the uncollectible amount or the amount in respect of which recovery has ceased to be probable is recognised as an expense, rather than as an adjustment of the amount of revenue originally recognised.” With respect to both of the VMS sales at issue, the accounting treatment that HP proposes is clearly inconsistent with IAS 18 and, therefore, wrong.

Q2 2009 (sale of software)